The Deflation / Inflation Balancing Act

Kurt Brouwer March 30th, 2009

The Current Climate: The current climate is characterized primarily by fear of further losses. Investors are worried, jumpy and prone to dash for the exits. Investing in the stock market has been a losing proposition for the past 18 months. And, in fact, it has been a very poor decade or more for stocks. Cash is king and the rate on personal savings is climbing (see A Bigger Mountain of Cash).

Though stocks have been hard hit, other assets have been struggling as well. Real estate prices peaked a few years ago and have been falling steadily, with some areas experiencing declines of 40% or more. Real estate sales volume has perked up a bit, but this rebound has been driven largely by sales of foreclosed properties.

Other than U.S. Treasury bonds, the bond market struggled last year, although it is beginning to bounce back a bit as the fears of financial contagion ease a bit. In other words, we have seen falling prices for most assets that we might hold, from stocks to real estate to bonds.

The Congressional Budget Office made this statement in the summary section of its recent report on the President’s Budget [emphasis added]:

…For the next two years, CBO anticipates that economic output will average about 7 percent below its potential-the output that would be produced if the economy’s resources were fully employed. That shortfall is comparable with the one that occurred during the recession of 1981 and 1982 and will persist for significantly longer-making the current recession the most severe since World War II. In CBO’s forecast, the unemployment rate peaks at 9.4 percent in late 2009 and early 2010 and remains above 7.0 percent through the end of 2011. With a large and sustained output gap, inflation is expected to be very low during the next several years…

The government is fighting hard to stave off further deflation of asset prices. However, this extraordinary effort to fight off deflation is likely to lead to higher inflation in the future.

The CBO estimates that inflation will be very low for ‘the next several years’ due to the output gap mentioned in the quotation above. That is, if global GDP is 7% below potential then there should not be a lot of pressure on pricing until the output gap is closed. All things being equal, I think that premise would be correct. However, just as economic output is falling, so is global capacity.

Factories are laying off workers and, in some cases, shutting down. Airlines are mothballing jets. Due to low energy prices, oil exploration is slowing. And so on. So, when the recovery does begin, the supply of goods and services will be curtailed for quite some time and that may lead to a faster uptake on prices than the CBO estimates.

This column from the Financial Times adds to this point [emphasis added]:

…The British economist Peter Warburton of Economic Perspectives raises fresh doubts about the output gap in an intriguing new paper (“Making the Case for an Early Return of Inflation”). Mr Warburton argues the expansion of global trade over the past couple of decades exerted downward pressure on inflation. During the boom years, the global supply chain was tuned to perfection, he says. The credit crisis, however, has fractured this supply chain; companies have gone bust, working capital has been hard to come by, and inventories have been run down. As a result, the productive capacity of the global economy has shrunk and the world has become more inflation prone. “An aggressive stimulus package to aggregate demand,” writes Mr Warburton, “which seeks to restore the status quo ante will encounter inflationary tendencies at lower levels of activity than before”.

This point is a good one in that our economic capacity to produce goods and services is falling and likely to fall further. Also, the extraordinary amount of debt our government is incurring, plus the high levels of government spending and other factors are likely to lead to higher demand from a weakened supply chain. We believe inflation will be the inevitable result.

And, that leads us to a discussion of the environment we expect to be in when this deflationary period ends:

The New Climate: As the financial panic subsides, we believe the future state of the financial markets will be very different from the current one. For a while, the two views - Current Climate or New Climate - will exist side by side, but, gradually, we believe the new climate will take form.

Here are four points that emphasize the new fiscal reality in Washington:

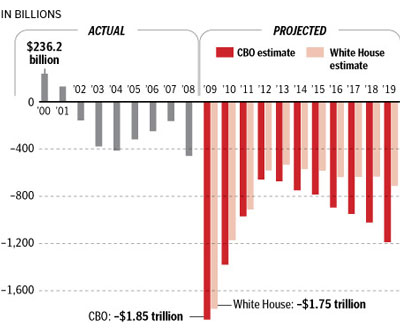

- The Congressional Budget Office estimates the budget deficit for fiscal year 2009 will be $1.75 trillion.

- CBO estimates that the budget deficit for fiscal year 2010 will be $1.1 trillion

- Future deficits will approximate $1 trillion per year for the foreseeable future.

- Government debt levels will double as a percentage of overall economic activity.

From the CBO report referenced above, we see this estimate of future deficits and increases in national debt:

…The cumulative deficit from 2010 to 2019 under the President’s proposals would total $9.3 trillion, compared with a cumulative deficit of $4.4 trillion projected under the current-law assumptions embodied in CBO’s baseline. Debt held by the public would rise, from 41 percent of GDP in 2008 to 57 percent in 2009 and then to 82 percent of GDP by 2019 (compared with 56 percent of GDP in that year under baseline assumptions)…

The government is incurring debt and ‘printing’ new money at a faster rate than we have seen since World War II. One likely result of this will be budget deficits and pressure for higher taxes - income taxes, corporate taxes, gas taxes and sales taxes. Assuming we have higher tax rates, this will have a negative impact, as it always has, on future economic growth.

This chart from the Washington Post illustrates what we have in store when it comes to Federal budget deficits.The right side of the following chart compares the CBO’s projection for future budget deficits with the White House projections. The left side shows the deficits for previous years, many of which seemed very high at the time. Now, they seem pretty modest by comparison.

Source: Washington Post

An excellent post from the Foundry blog illustrates that this deficit debacle has been a bipartisan project:

- President Bush expanded the federal budget by a historic $700 billion through 2008. President Obama would add another $1 trillion.

- President Bush began a string of expensive financial bailouts. President Obama is accelerating that course.

- President Bush created a Medicare drug entitlement that will cost an estimated $800 billion in its first decade. President Obama has proposed a $634 billion down payment on a new government health care fund.

- President Bush increased federal education spending 58 percent faster than inflation. President Obama would double it.

- President Bush became the first President to spend 3 percent of GDP on federal antipoverty programs. President Obama has already increased this spending by 20 percent.

- President Bush tilted the income tax burden more toward upper-income taxpayers. President Obama would continue that trend.

- President Bush presided over a $2.5 trillion increase in the public debt through 2008. Setting aside 2009 (for which Presidents Bush and Obama share responsibility for an additional $2.6 trillion in public debt), President Obama’s budget would add $4.9 trillion in public debt from the beginning of 2010 through 2016.

After a recession of this severity and duration, we would normally see a strong and vibrant economic recovery. However, that may not happen this time for several reasons. First, once the economy recovers, inflation will rear its head and the Federal Reserve will have to pull back from its extreme position of injecting liquidity into the financial system. When it does, the economic upturn will slow. Also, the ballooning budget deficits will eventually take a toll and government funding for new and existing programs will eventually slow down.

Real estate construction will probably remain at current low levels for a while as the inventory of unsold homes, empty offices and vacant storefronts slowly gets worked down. Therefore, growth in employment from construction will be slow.

The economic recovery overseas will likely lag that of the United States, so our economy will be trying to grow without much help from our major trading partners.

So, we do see an economic recovery on the horizon. However, it will probably not be a robust recovery, but a more moderate one.

The Transition: We believe the financial markets are forward-looking, reflecting the state of the economy many months out. The Current Climate is one of doom, gloom and deflation. Companies are going under, loans are being called, prices for a broad range of assets are weak. However, eventually, the current climate will run its course.

Assuming governmental policy makers make positive progress in cleaning up the banking mess and getting the credit markets functioning again, we believe both the fixed income and equity markets could stage strong rallies over the next two years. As that recovery happens, we will begin the transition into the New Climate, which will be very different from the Current Climate.

The New Climate: The new climate will feature higher inflation and higher long-term interest rates. We believe portfolios will have to evolve over the course of the next year or two to be responsive to this new environment. Bonds, especially those with fixed rates and longer maturities, have done poorly in past inflations. Treasury Inflation Protected Securities are one solution. Equities have historically been good inflation hedges. Other opportunities that should benefit from rising inflation would be energy and commodity-related investments.

One complicating factor is the strength of the U.S. dollar, which rebounded quite nicely as energy prices fell last year. Also, the dollar benefited from the global flight to quality, which primarily involved the purchase of Treasury securities.

However, recent actions such as the announcement of enormous U.S. Treasury purchases have reignited fears that our government is going too far. As such, we have to evaluate future pressures on the dollar when and if inflation comes back.

As we can see from this chart, inflation expectations have already rebounded a bit from the extremely low levels we saw a few months ago. This chart shows the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds minus the yield on 10-year Treasury Inflation Protected securities:

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve, U.S. Treasury, Capital Spectator

Last year, in response to the challenging credit conditions, yields on U.S. Treasury bonds fell dramatically. As a result, the implied inflation rate (Treasury bond yield minus TIPS yield) fell precipitously. It has climbed back up a ways to about 1.5%, but it is still far from the rate of early last year.

This has been a very challenging period and the current climate — characterized by low inflation, falling asset prices and weak economic output — is not yet behind us. This climate poses its main risk in falling prices for assets of all types.

However, we also see new challenges - such as higher inflation - on the horizon. Facing up to those potential challenges will require a new strategy for the new climate that appears to be ‘baked in’ to the economic and financial solutions our government is pursuing.

For more on these topics:

- Are We Talking Great Depression?

- Are We Talking Great Depression? (Part 2)

- Pimco Predicts Inflation Ahead

- Business , Economy , Geopolitics , Investing , Money , Personal Finance , income taxes , inflation

- Comments(3)